Patent number US 11992411 describes a medical device engineered to assist in the attachment of lower limb prosthetics directly to a patient’s bone. The patent was recently granted to a former graduate student and his professor for work completed during his master’s degree program at Colorado State University.

Adam Morrone, currently a systems engineer at Lockheed Martin and former CSU mechanical engineering master student, and Steve Simske, professor of systems engineering, completed research for the patent in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. The patent was granted May 28.

Traditional prosthetics rely on technology that cups the end of a limb, placing bodyweight pressure on soft tissue, not the skeletal system. When bones do not experience tension from musculature or impact from use, they can experience osteoporosis, making them brittle and subject to breakage. Integrated prosthetic technology has made strides in recent years, allowing patients and medical professionals to find more effective ways to help amputees maintain bone health, and increase sensory feedback and stability. It involves many lines of biomedical research, including connections with skin, muscles, and the nervous system. Morrone’s and Simske’s device is called a coupler, the synthetic connection between a prosthetic and the rest of a body.

“Focusing on the bone was something I felt equipped to research,” Morrone said. “There are other issues with Integrated prosthetics, like getting the skin to heal around the opening, but I wanted to focus on how to get the bone to grow into the coupler to provide the rigid support we are accustomed to.”

Other key benefits of the device

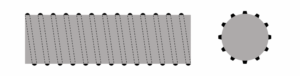

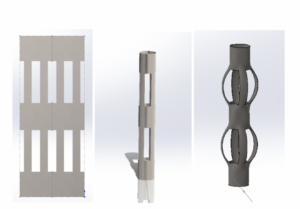

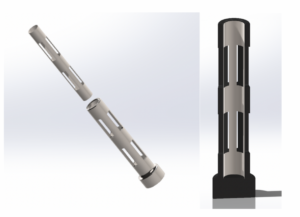

The device leverages a “shape memory alloy,” a metal that can change properties depending on its temperature, to anchor a prosthetic coupling device more effectively within a bone. Other comparable coupling devices used today are inserted into drilled-out bones, like a femur, using “press fit” methods, which involve forcing or pounding the device into the bone. Morrone’s and Simske’s device could be inserted and then rely on the person’s body temperature to reshape and anchor it into their bone.

Another advantage is how the alloy can adjust over time to bone changes. Current devices are ribbed to create areas of high and low pressure against the bone. Bone recedes from high pressure while it grows into areas of low-pressure, a delicate balance that might result in the coupler becoming too loose before the bone has a chance to adequately grow. This device places a constant and dynamic pressure that can follow receding bone, maintaining tightness while allowing more time for the bone to grow.

The alloy the researchers used, nickel-titanium (nitinol), is highly biocompatible and widely used for medical purposes. One of Morrone’s biggest challenges was in producing thick foil strips that could take full advantage of the material’s elastic range while maintaining the desired shape. This was the focus of his thesis, parts of which were published with his advisor, Simske, as co-author.

Morrone said he’s not certain of the future of his patent, whether it would even be used given the amount of work it takes to bring a new medical device to market. But he said he’s gratified to have contributed to the advancement of science.

“Research is important to me, always has been,” he said. “And maybe this will help other researchers spark ideas in the future. Having the government tell me that we did something unique is a nice gold star.”

The device is not limited to medical applications. According to the patent, it can also connect various mechanical components, particularly those that may need replacement during their lifecycles.

Mastery and mentorship

Morrone started his education as an undergraduate computer engineering student at Liberty University in Virginia, but he soon became interested in soft robotics and 3D printing. His interest led him to design prosthetic limbs that could be printed and made functional with control sensors attached to users’ muscles. He liked this line of research so much that he decided to shift career paths to specialize in biomedical engineering, becoming Simske’s first graduate student at CSU.

Simske, known for having more than 240 patents to his name, is an expert in data analysis, AI, and systems engineering. Simske and Morrone worked on several projects and published papers focused on data analysis for security and machine learning. Simske has worked with shape memory alloys for more than 30 years and was among the first to implant them in rabbit cranial bones with a surgery approach he created in 1995. He worked at HP as an accomplished researcher for 24 years.

“Adam was an ideal first student for me to have at CSU. At HP, I worked with dozens of highly creative engineers around the world, all of whom shared Adam’s independent spirit, thirst to get things done, and broad interdisciplinary training,” Simske said. “The CSU biomedical staff and director did a great job getting S-tier students such as Adam into the interviewing process.

“That being said, Adam is a singleton in many ways, a rare combination of dedication to getting research done and sharing it with other, usually younger students.”

Morrone said he was grateful for Simske’s mentorship and support.

“Steve is great at letting his grad students run with things. His expertise was in clearing the path and clearing the obstacles,” he said. “I came in pretty passionate about these things, Steve was just like, ‘Let’s do it!’”

Immediately following graduation, Morrone faced a tough job market due to the pandemic. A job offer with a medical devices company was rescinded, so he had to look elsewhere. Taking his expertise in data analysis, he landed his current position in the aerospace industry, representing yet another shift in his career focus. He now researches advanced quantum technology for sensing and communication architecture.

Morrone’s time in academia was characterized by taking on multidisciplinary projects, leading him to a dynamic set of skills and experiences. His advice to those following a similar path is to take full advantage of what academia has to offer, and not to delay if they have a choice.

“It helped me to explore widely when I was in school, and opportunities like that get harder to find as you get further into a career,” he said. “Academia is a very exciting environment; you get access to a lot of different interesting things.”