When the Walton Family Foundation solicited proposals to enhance research and development efforts on nature-based storage in the Colorado River Watershed, Ellen Wohl didn’t hesitate to submit a proposal. The award-winning fluvial geomorphologist secured the award and got to work.

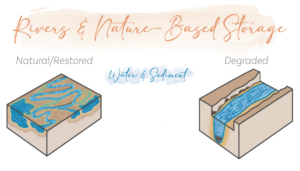

The foundation needed an informational resource and document repository of existing research on nature-based storage: the slowing of rivers and streams through natural means (i.e., beaver dams, log jams, etc.) to allow the storage of water, sediment, and organic carbon.

Wohl, University Distinguished Professor of Geosciences, collaborated with faculty from the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on the research, then enlisted the expertise of the One Water Solutions Institute team to provide the programming and web development.

The final product is the nature-based storage dashboard, now live and in need of participation from the river restoration community to populate the database, benefitting the industry and furthering the science.

Why nature-based storage?

River systems often have steep narrow segments of fast-moving water, known as ‘strings’, that eventually flow into a flat meadow or floodplain where the stream slows and meanders, known as ‘beads’. Wohl worked with Associate Professor Ryan Morrison and his graduate student Evan Schulz to map the distribution of river strings versus beads in the Upper Colorado River Basin.

“We found the beads with more geomorphic complexity stored order of magnitude more water than the steep narrow string sections,” said Morrison. “Complexity and variability are important for ecosystem health, much like eating a variety of foods is healthier than eating one type of food every day.”

Associate Professor Ryan Bailey and his graduate student Muhammad Raffae joined the project and mapped the groundwater and sediment storage capacity of strings and beads in the river basin. Their research used a groundwater module for the widely used Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) to better estimate river basin storage. The module was created by Bailey, who specializes in groundwater hydrology and develops software to improve the assessment of watersheds around the world.

“My group provided groundwater and sediment storage estimates for the Colorado River Basin, using the hydrologic model SWAT+,” said Bailey. “I really enjoyed working with Ellen Wohl and the Geosciences group. We learned a lot in this interdisciplinary research.”

The One Water Solutions Institute effect

For Wohl, explaining the science behind nature-based storage was not a challenge, but creating a website and developing a database was another story.

“We needed the online resource to be free and publicly accessible, but how to do that was beyond my capabilities,” said Wohl.

Programming and software development is an area of expertise for the One Water Solutions Institute. Associate Director for Software Innovation Tyler Wible worked closely with Wohl to create the public-facing nature-based storage dashboard, including the framework for collecting data submissions from external users.

“The dashboard is the starting point of a deeper dive into the research and can serve as the first step of a literature review for a graduate student’s research, or as a resource for a consultant seeking insight on a project,” said Wible. “There are many ways to leverage this resource as a centralized collection of data provided at no cost.”

Wible’s role at the institute often involves centralizing disparate data to improve efficiency, such as his work with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment to streamline data collection for compliance with the Clean Water Act.

“Their expertise was critical in getting the information out there in an accessible way,” said Wohl.

Getting on the same page

The dashboard explains nature-based storage, provides tools for implementing projects, and suggests best practices for pre- and post-implementation monitoring. The dashboard also serves as a project database where researchers, practitioners, and government agencies can enter their project details including monitoring data and any outcomes.

“One of the biggest criticisms of river restoration is we make the same mistakes over and over. A restoration project is funded and completed, but includes limited monitoring,” said Wohl. “There was not a central place to access what had been done, detailing what worked and what didn’t.”

Wohl recognized the need for a centralized database after working with an undergraduate engineering student to compile river restoration projects in Colorado.

“We ended up abandoning the idea because it was so difficult to find records of these projects,” Wohl said. “Many projects are performed by private consulting firms and because there is no standardization in reporting, you don’t know who did what, where, or when.”

Wohl worked with practitioners as well as state and county regulators to develop the monitoring protocols to ensure they were practical and accessible to everyone.