Jeff Collett had a problem.

His tiny high school in Rockaway, Oregon, had no physics teacher. The previous instructor had passed away, and his school wasn’t going to rehire.

So, 17-year-old Jeff asked his school board for a teacher.

It would be lucky for Colorado State University that he got one.

This month, CSU bestowed Collett with the honor of University Distinguished Professor in Atmospheric Science. Typically, only 20 or so faculty members across all eight colleges carry the distinction at any one time.

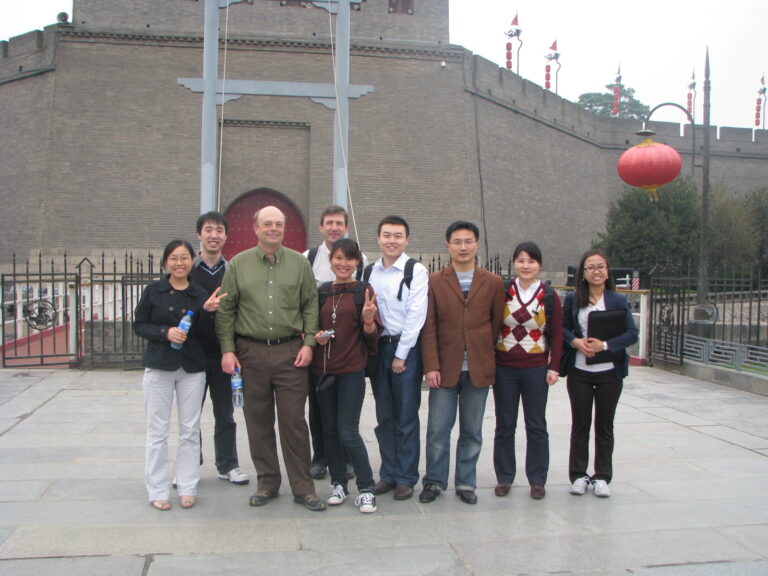

Collett’s research focuses on understanding the chemical composition of fog and clouds and helping communities and agencies address environmental air quality concerns. He has worked extensively with the National Park Service — studying the impacts of pollution from urban areas, agriculture, oil and gas development and wildfire smoke in pristine areas, including studies in national parks such as Rocky Mountain, Grand Teton, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, Big Bend and Carlsbad Caverns. He also collaborates with cities, towns and counties across Colorado to capture and measure air quality impacts of oil and gas development. In recent years, he has collaborated extensively in China, a region with some of the world’s worst air pollution.

“His work truly embodies the land-grant ideal of cutting-edge research with community impact,” said fellow Atmospheric Science University Distinguished Professor Sonia Kreidenweis.

You either have chemistry or you don’t

Growing up on the Oregon coast outside of a town with 250 people gave Collett an appreciation for the environment and environmental science.

That small school experience meant he was also the only student in second-year chemistry, so he could get away with a lot. Like building a glass tube blowgun to blow darts across the lab, documenting principles of accuracy or precision (or the lack thereof). He also sheepishly admits evacuating part of his high school with a prank involving a tiny bit of a very smelly substance.

His instructor was complicit, but never confessed that Collett was involved, Collett said with a grin. “We had a good time. There were a few perks like that.”

He received his chemical engineering degree from MIT, and a master’s and Ph.D. in environmental engineering science from Caltech. Before joining CSU in 1994, he worked as a post-doc in the Laboratory for Atmospheric Physics at ETH-Zurich and three years as an assistant professor at the University of Illinois in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

He has now spent almost 30 years at one of the top atmospheric science departments in the country.

He started his work examining how trace gases and atmospheric particles are chemically and physically transformed through interactions with clouds and fogs — a place few other people had explored. During his post-doc he expanded this work to study how pollutants scavenged by cloud drops were incorporated into snow crystals that carried them to the surface.

“Jeff is one of only a few people in the world developing and applying technology to study the composition of clouds and fog, which have been shown to be excellent chemical reactors for processing particles and gases in the atmosphere,” Kreidenweis said. “In many regions, fogs are a major pathway for deposition of pollutants to earth’s surface, yet fogs are difficult to forecast and difficult to sample.”

Building a legacy for CSU

Collett and Kreidenweis helped build a fledgling Atmospheric Chemistry/Air Quality program into a powerhouse that has since attracted more researchers and led to collaborations across campus. They include fellow Atmospheric Science + Chemistry UDP A.R. “Ravi” Ravishankara; Jeff Pierce and Emily Fischer in Atmospheric Science; Tami Bond, Shantanu Jathar and John Volckens in Mechanical Engineering; Ellison Carter in Civil and Environmental Engineering; Jay Ham in Soil and Crop Sciences, and Delphine Farmer, Megan Willis and Chuck Henry in Chemistry, among others.

More recently, Collett’s work has expanded into studying nitrogen pollution, and oil and gas emissions.

“The work on nitrogen pollution we’ve been doing over the last 20 years,” Collett said. “This is looking at reactive forms of nitrogen in the atmosphere from industry, traffic and agriculture, how that moves through the atmosphere, how it’s transferred and deposited. While emissions of nitrogen oxides are closely regulated, emissions of ammonia are largely unregulated and constitute an increasing fraction of nitrogen inputs to sensitive ecosystems.”

“We’ve raised visibility working on this issue, but we haven’t seen emissions of ammonia going down,” he said. “That remains a challenge.”

Collett’s work on oil and gas has focused on emissions of air toxics and precursors to ozone and fine particle haze formation. His work, some in collaboration with colleague Emily Fischer, has pointed to the impacts of oil and gas development on formation of visibility-reducing haze and ozone in national parks from New Mexico to North Dakota.

He and his team have also published ground-breaking research characterizing emissions of benzene and other air toxics during oil and gas well drilling and completions. Earlier studies by his team supported a health risk assessment for people living near oil and gas development in Colorado that had a major influence on the state’s decision to increase setback distances for new wells to 2,000 feet. He is often quoted by media outlets because of his expertise, including work with communities in the northern Front Range and on Colorado’s Western Slope.

Helping the next generation

Fittingly, Collett can watch his clouds from his corner office on the Foothills Campus that overlooks the university’s solar plant. His walls feature Ansel Adams portraits of Yosemite, where he did his doctorate on pollutant deposition via cloud interception and subsequent work with Kreidenweis at CSU on wildfire haze.

A glass award chiseled with “6th International Conference on Fog” sits on the windowsill. Collett served as scientific chair for that conference in Yokohama and he hosted the 9th triennial conference at CSU in 2023.

When he’s not in the office, Collett spends time hiking and skiing in Summit County with his family. He met his wife in grad school at Caltech, and both sons followed their parents into science and engineering.

Like those days in high school chemistry, he’s still experimenting. He is particularly proud of his team for creating instrumentation like fog collectors to help scientists in the field and new chemical analysis techniques to help them in the lab.

And yes, fog still fascinates him. “The people who study fog represent a small community of diverse interests,” he said. “In addition to their effects on atmospheric chemistry and air quality, fogs greatly impact transportation, are difficult to forecast, provide important hydrological inputs to unique ecosystems like the redwood forests of northern California, and are harvested for drinking water in arid regions around the world, from Chile to Namibia.”

Like many people, he didn’t always know where his career was headed. His advice for the next-generation and incoming graduate students?

“Do something you enjoy,” Collett said. “There are lots of decision points in your career, you often face multiple good choices, and it’s hard to know where your path’s going to take you. At various points, I thought: ‘Do I want to go to grad school? Go into industry? Pursue an academic career?’ I wound up going to Switzerland to do a post-doc. That was a wonderful experience, personally and professionally. It exposed me to other cultures and helped train me in new areas that opened future opportunities.”