Cameron Peak Fire yields collaboration, new discoveries and more questions

story by Jayme DeLoss

published July 31, 2023

As the largest wildfire in Colorado history was burning west of Fort Collins in 2020, Colorado State University researchers were making plans to study its effects on the local watershed. As soon as they were permitted in the burn area – before the Cameron Peak Fire was completely extinguished – they were collecting data and making discoveries.

Hydrologist Stephanie Kampf assembled an interdisciplinary team of researchers and received a Rapid Response Research grant from the National Science Foundation in the fall of 2020 to study waterways affected by the Cameron Peak Fire.

Kampf, who is a professor of watershed science in the Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability, already had been monitoring waterways in the area. After replacing most of her equipment that had been destroyed by the fire, she was back to work, studying streamflow, sediments and snow.

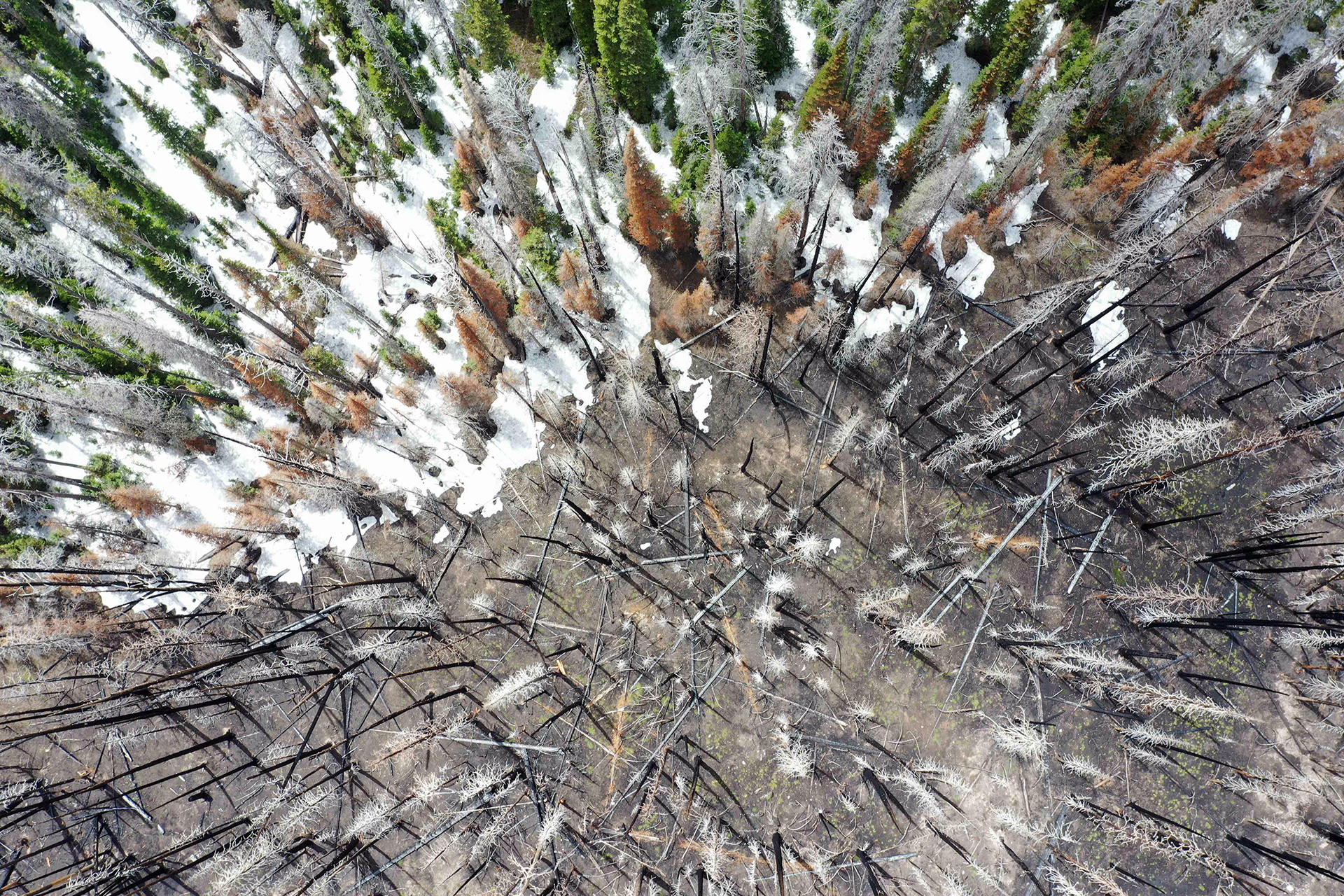

The Cameron Peak Fire was remarkable in its size – burning more than 208,000 acres – but also its location. Historically, high-elevation fires have been rare, so their effects were largely unknown.

In Colorado and other parts of the U.S. West, mountain snowpack serves as a natural reservoir, and the fire had serious implications for the Northern Colorado water supply.

“We had hypothesized that there would be an impact on snow, but we were surprised at how large the impact was,” Kampf said.

Less snow and faster melt

In papers published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and Geophysical Research Letters, Kampf, Dan McGrath, an assistant professor of Geosciences, and their collaborators found a decrease in the amount of snow that accumulated in the burn area and an increase in the melt rate.

Without tree cover to shade the ground, snow in direct sun melts faster. Soot that falls from burned trees darkens the snow surface, and darker surfaces absorb more energy from the sun.

At high elevations, the snowpack melted up to 13 days earlier in burned areas than unburned areas. Lower-elevation burn scars were snow free 27 days sooner. Snow melt timing affects streamflow, and streamflow timing is important for water management.

“Cities and farmers count on the reliable delivery of water from snowmelt throughout the spring and summer months, so an offset of two or more weeks can be a big challenge for water managers,” McGrath said.

Earlier melt means less water is available later in the season, and dry conditions make it harder for the landscape to recover. Lower soil moisture late in the season could kill new seedlings and prevent vegetation from growing back in the burn scar.

“In a warming climate, we are seeing less snow and earlier snowmelt independent of fires, which leads to a dry landscape that is prone to increased wildfire activity,” McGrath said.

Late-season snow prevents worst-case scenario

Late-season snow, a regular occurrence at high elevations in Colorado, helps preserve snowpack by temporarily burying the soot-covered snow and lowering melt rates.

“That can help mute the impacts compared to other fire-impacted regions, at least for the time being,” McGrath said.

The late-season snow buffer won’t endure a warming climate, he said, as snow will turn to rain in the shoulder seasons. He added that every climate zone and snow regime has different factors. Lower latitude and lower elevation mountain ranges in the West already don’t benefit from late-season snow because of warmer air temperatures.

New questions

Studying the effects of the Cameron Peak Fire has led to many more questions about how wildfire impacts vary across complex terrain and over the wide range of elevations in the burn scar.

“There’s a lot of complex topography in these environments,” McGrath said, “and no previous studies have examined that in detail.”

McGrath is exploring how impacts vary between north- and south-facing slopes, based on observations that south-facing slopes sustain the most acute impacts in lower snow accumulation and earlier melt. With colleagues from the Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory, he also will look into how the health of the forest before the fire might impact the long-term recovery of the snowpack. Healthier trees can have more superficial burns, whereas beetle-killed trees might shed soot for a long time.

“These fires have immediate impacts, but they also have long tails,” McGrath said. “Until the point when a forest regrows that can shade the snowpack again, many of these impacts will persist.”

Kampf will lead a new $725,000 NSF-funded study investigating the difference between high-elevation and low-elevation fire response. At lower elevations, she has observed that rain can flood streams and create debris flows after a fire. These effects are not seen at higher elevations, but landslides are more likely, she noted.

Flashfloods, debris flows and water quality problems from sediment are post-fire hazards Kampf hopes to address through her research.

“Our hope is that the research can help people know what to prioritize in future fires because we know that there will be more fires,” Kampf said.

Proactive water management

While Kampf, McGrath and others have been looking at post-fire changes in water quantity, Matt Ross and his team have been investigating changes in water quality. Ross, an assistant professor of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability, is interested in the short- and long-term effects on water quality after a wildfire.

Ross’ lab studies the Poudre River from the headwaters nearly to Greeley. In the short term, they have observed more sediment in the water, which is expected after a fire, as charred forest remnants are flushed downstream.

Sediment can impact cities’ ability to treat drinking water, so the City of Fort Collins monitors the amount of sediment in the Poudre River and can shut off intake from the river when sediment levels are too high, relying on water from Horsetooth Reservoir instead.

With sediment comes the nutrient phosphorus, which is often bound to sediment particles. Fire also disrupts the nitrogen cycle. Previous research by Chuck Rhoades, a scientist at the Rocky Mountain Research Station and frequent collaborator with CSU, shows that nitrogen levels can remain high for decades after fire. Excess nutrients can degrade water quality and cause algae blooms in rivers and reservoirs. Algae can make it difficult for water managers to treat the water and cause water to have an undesirable taste and smell.

Ross and his team haven’t observed any large, problematic algae blooms in the wake of the Cameron Peak Fire, but they are working with the cities of Fort Collins and Greeley and others to continue to monitor nutrients and algae dynamics in the river and the reservoirs that supply it, helping these cities be proactive in their water resource management.

“The cities in the Front Range are super proactive,” Ross said. “We thought about this research project long before the fire because they wanted to make sure they were ahead of it.”

Algae blooms also can lead to anoxic events, a concern for fish and recreation. When algae is able to grow exponentially on abundant nutrients, it will eventually die, creating an environment where other microbes consume the dead algae and all of the oxygen in the water. These low-oxygen events can cause ecosystem problems and kill fish.

“The cities in the Front Range are super proactive. We thought about this research project long before the fire because they wanted to make sure they were ahead of it.”

— Matt Ross, assistant professor of ecosystem science and sustainability

A remaining question, Ross noted, is to what extent sediment is limiting mountain reservoirs’ capacity to store water? Together, the Cameron Peak and High Park burn areas constitute a large percentage of Northern Colorado’s water supply, and lessons learned from these fires will help water managers across the U.S. West.

“This research helps us proactively think about managing a resilient future,” Ross said. “Other cities can be proactive in the same way that our water managers have been. Wildfire is part of the landscape, and it’s only going to intensify. We have to be able to plan for it and think more critically about the intersections of fire and water supply.”

How much mulch?

Peter Nelson worked with the City of Greeley, with funding from the Colorado Water Conservation Board, to study the effectiveness of dropping mulch on fire-impacted slopes to reduce runoff. Credit: Peter Nelson

One strategy for protecting water quality is to drop shredded wood from helicopters onto steep slopes most at risk of sediment runoff. Peter Nelson, an associate professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, has been studying the effectiveness of this practice.

Mulching to reduce sediment runoff has been studied in the past on small scales but never at the watershed scale. To measure erosion and deposition at the watershed scale, Nelson’s research group uses drones to survey the large study area.

They compared three mulched and three unmulched watersheds through a series of drone images repeated over time. Their findings suggest that mulch is not the most important factor in the rate of erosion. Steeper slopes had more erosion, whether they were mulched or not. Rainfall intensity also played a big role.

They found that the overall concentration at which mulch is applied could be important, as well as where on the slope it’s applied.

“That’s challenging because they’re dropping these piles of wood from helicopters, so trying to get the mulch in a specific place at a specific coverage is going to be hard for even the most experienced helicopter pilots,” Nelson said.

His group continues to work on developing recommendations for best practices.

Nature knows best

Ryan Morrison, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, is working with other researchers on multiple projects in the Cameron Peak burn area, exploring impacts and natural restoration techniques. He is also examining effects on aquatic ecology and food webs with CSU ecologists Dan Preston and Yoichiro Kanno.

With University Distinguished Professor Ellen Wohl, Morrison has investigated how a watershed’s characteristics can make it resilient to disturbances like fire. They have found that naturally occurring large wood in a system, such as logjams, can filter sediment and slow down overall flow that could contribute to flooding.

“In a sense, these catchments are like a natural infrastructure that can protect humans if they’re managed correctly,” Morrison said.

“In a sense, these catchments are like a natural infrastructure that can protect humans if they’re managed correctly.”

— Ryan Morrison, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering

His research group is working with the Coalition for the Poudre River Watershed to monitor recovery efforts and gauge their effectiveness.

“There are a lot of good people working up there,” Morrison said. “There have been a lot of good collaborators outside of CSU as well. Chuck Rhoades with the Rocky Mountain Research Station, folks at the Coalition for the Poudre River Watershed and the City – just great people all around who are interested in learning from the fire and trying to improve the resiliency of the watershed moving forward.”

Changing landscape

As the researchers watch the landscape recover from the Cameron Peak Fire, one question is on all of their minds: Will it ever be the same? Will grasslands replace forests? This has happened in some lower elevation burn zones, but it remains to be seen what will happen at higher elevations.

“Sometimes the forest doesn’t come back the same at all,” Morrison said. “With climate change, it might not make sense to replant what was there.”

Faculty members Sean Gallen and Sara Rathburn (Geosciences), Paul Evangelista and Tony Vorster (Natural Resource Ecology Lab), Steven Fassnacht (Ecosystem Science and Sustainability), Camille Stevens-Rumann (Forest and Rangeland Stewardship) and Kristen Rasmussen (Atmospheric Science) contributed to these studies.

Summers of Smoke

For decades, Colorado State University has been at the forefront of fire science, earning its reputation as one of the leading institutions studying wildfires. Explore other stories on wildfire research at CSU.