As COVID-19 cases start to climb again in Colorado, public health officials are seeking a scientific gauge to determine public policies and safety measures. Colorado State University researchers Susan De Long and Carol Wilusz will provide the indicator they need through a $520,000 project funded by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. The CSU team will study a readily available source that will give them valuable insights into the infection rate of specific communities: human feces.

Sampling wastewater is a cost-effective way to test entire communities. By studying the wastewater of communities including Fort Collins, Denver, Boulder, Estes Park and Colorado Springs, the scientists and engineers can track trends in infection rates over time.

The proof is in the poop

Those infected with coronavirus often don’t exhibit symptoms for 10 to 14 days, and some remain asymptomatic. Regardless of their symptoms, or lack of symptoms, within two days, they start shedding the virus in their feces. Detecting the amount of virus in a community’s waste stream can warn of an impending outbreak four days to two weeks in advance.

“We believe this could be a promising supplemental tool for helping predict an outbreak in a community, possibly a couple of days before, so we can shift additional resources to that area,” said Nicole Rowan, clean water program manager with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

So far, 16 wastewater districts have signed on to the project, constituting up to 65 percent of the state’s population. The districts will take samples twice a week and send them to CSU. All of the testing will be done at CSU’s Molecular Quantification Core facility, with the ambitious goal of delivering data to the state in three days or less.

“It’s going to be a really important dataset for our community that will help make decisions regarding public health recommendations for distancing status and shutdown status,” said De Long, an associate professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Wilusz, a professor and RNA biologist in the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology, pointed out how cost-effective this method will be, with tests costing only a few cents per person.

“We can test everyone in Fort Collins and it will cost pennies for each person,” she said.

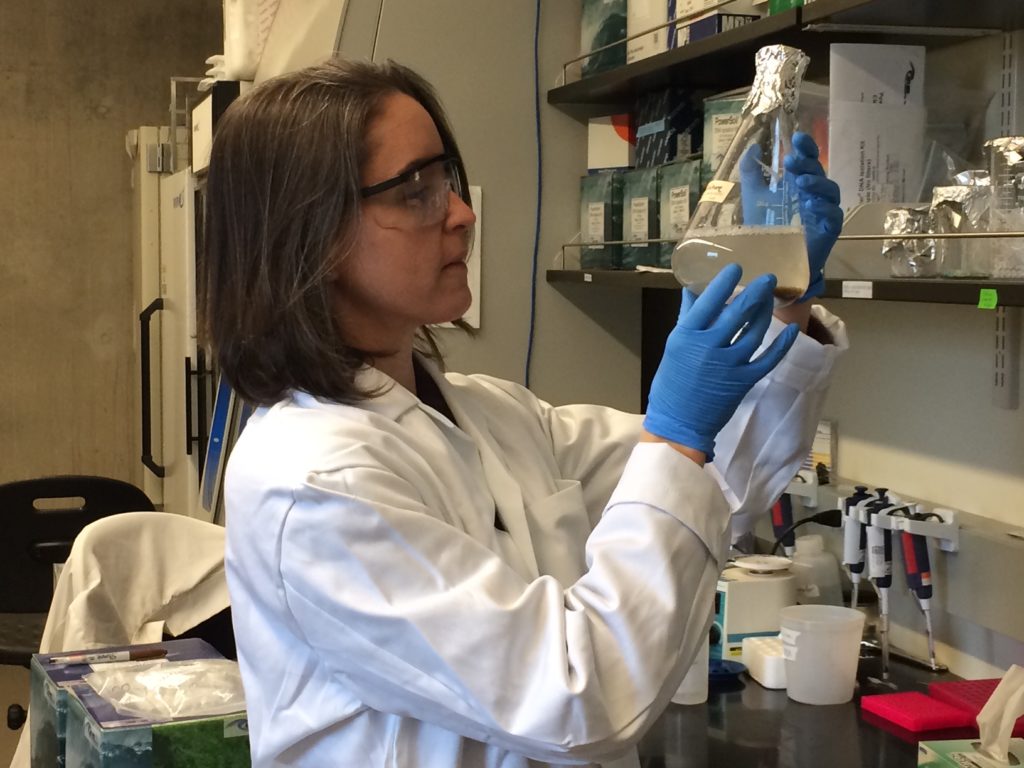

In the lab at CSU, a technician will filter the samples to remove solids, concentrate the viral particles that are dilute in wastewater, and extract nucleic acids from the viral particles. COVID-19 is an RNA virus, so researchers will extract the RNA and use enzymes to make DNA copies of the target specific to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

“Isolating RNA from sewage is something I never thought I’d be doing,” Wilusz said. “I’ve learned a lot more about sewage than I probably ever needed to know.”

CSU had the specialized technology in place to perform this testing, thanks to purchase of a digital PCR machine in 2015 by the Office of the Vice President for Research and other CSU units, including the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

“The technology we are using – digital droplet PCR – is ideal for this particular application because it is resistant to the types of inhibitors found in wastewater,” Wilusz said.

Public health agencies across the state will provide current case data for the project. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment will interpret all the data and convey what they’ve found to public health professionals working on the ongoing response.

The collaborative aims to make this information accessible with the help of Professor Mazdak Arabi, director of the One Water Solutions Institute at CSU. Arabi will create a GIS-based, interactive online map for displaying the data, incorporating socioeconomic insights to give deeper context to the results.

A grassroots effort

Wastewater epidemiology is not a novel concept. This method has been used to monitor polio and illegal drug use. In Colorado earlier this spring, some wastewater districts sent samples to an East Coast-based company for coronavirus testing, but it took several weeks to get results, negating any benefit from the data.

Jason Graham, Fort Collins director of plant operations, water reclamation and biosolids, instead contacted CSU to see if the testing and analysis could be done here. “My interest in bringing CSU in was to have a local partner, reduced costs and quicker turnaround time,” he said. “I always try to partner with CSU if possible.”

De Long saw an opportunity to expand the scope of the project beyond Fort Collins. If they were going to test local wastewater, why not also do this for the state? She reached out to Jim McQuarrie, director of strategy and innovation at Denver’s Metro Wastewater Reclamation District, and Liz Werth, laboratory support supervisor with Metro Wastewater, who already had organized a group of wastewater districts involved in COVID-19 testing. The CSU team was the solution to the high cost and long turnaround time that came with sending their samples out of state for analysis.

“This is the kind of thing we should be doing at CSU because we’re a land-grant university and we serve our community,” De Long said. Initially, she didn’t know whether she would be paid for the work or if she would be able to publish findings, but it didn’t matter.

“There’s a need here that we have the capacity to fill, we’re just going to do it,” she and her colleagues decided.

De Long and her colleagues put their summer plans on hold and got to work, thanks to $20,000 in seed funding from the Office of the Vice President for Research and donation of a $12,000 ultrafiltration device from Metro Wastewater Reclamation District.

De Long and Wilusz developed the protocol for this project with GT Molecular, a Fort Collins biotechnology company. GT Molecular will offer this testing service on their own to entities outside Colorado that are not covered by the project, and they are available to back up the CSU team, should the need arise.

Of the overall $520,000 contract, $490,000 will go to CSU. The rest will go to collaborator Metro State, which will support analyses and process some of the samples.

The light at the end of the sewage

Along with being a harbinger of rising COVID-19 cases, this detection method also will inform officials if there is a downward trend in infections.

“Not only is this an early warning signal for when things are getting worse, it’s a nice signal for when things are getting better,” De Long said.