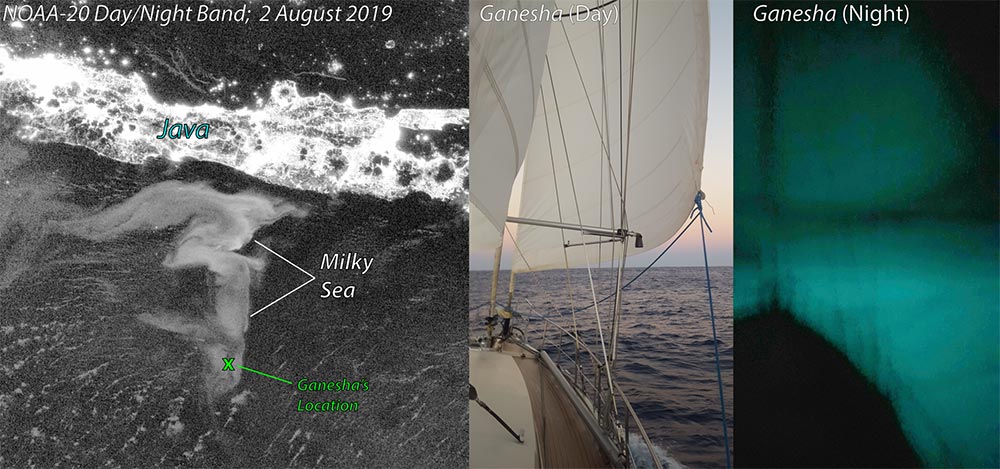

A 100,000-square-kilometer bioluminescent milky sea south of Java, as seen from space on Aug. 2, 2019, and from the Earth’s surface by the private yacht Ganesha. In the nighttime photo, the first of its kind, the ship’s deck appears as a dark silhouette against the glowing waters.

Credit: Steven Miller/Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere at CSU

Milky seas – the rare phenomenon of glowing areas on the ocean’s surface that can cover thousands of square miles – are not new to scientists at Colorado State University. They have previously demonstrated the use of satellites to see these elusive phenomena. What was missing were photographic observations of milky seas observed from the Earth’s surface and from space at the same time.

Until now.

In a new paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Steven Miller, professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science and director of CSU’s Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, compares satellite observations of a 2019 milky sea event off the coast of Java, to photographic evidence from the sailing ship Ganesha, a 16-meter private yacht. The yacht happened to be sailing in the milky seas at the same time. Unsure of what they had encountered, the yacht’s crew provided CSU their enlightening footage after learning of its expertise in satellite observations, and Miller’s particular interest in capturing milky seas from space.

Miller has previously compared satellite observations to tales from maritime lore to try to understand how the rarely-encountered mystery of the deep works.

Can we observe milky seas up close?

The crew of the Ganesha described the sea as a “luminous snowfield.” A crew member recounted what she saw: “Both the color and intensity of the glow was akin to glow-in-the-dark stars/stickers, or some watches that have glowing parts on the hands…a very soft glow that was gentle on the eyes.”

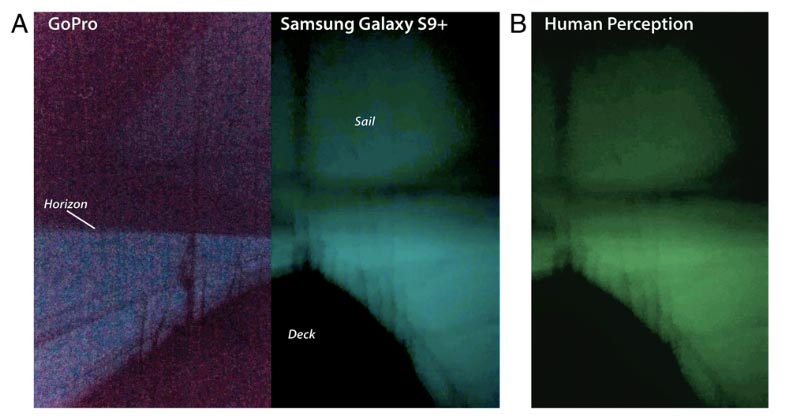

GoPro and smartphone photographs clearly show the glow of the ocean, spreading from horizon to horizon, shining through the rails of the boat. A comparison image that has been edited to reflect the perception of the crew at the time accounts for difficulties in capturing such low-light signals on commercial, non-optimized photographic hardware.

Digital photography of the 2019 Java milky sea, captured by the Ganesha crew. The image shows a view of (A) the ship’s prow and (B) a color-adjusted version of the Samsung photo approximating the visual perception of the glow.

According to the captain of the Ganesha, the glow appeared to be emanating from a fair depth below the ocean’s surface – perhaps as deep as 30 feet. A bucket of water that was drawn from the glowing sea contained many pinpoints of steady light, instead of the flashing or sparkling light observed by more commonly experienced forms of marine bioluminescence. As described briefly in the paper, this sheds some light onto the hypotheses of milky seas. Some ideas for milky sea formation suggest a “surface slick” of bioluminescence, but the observations from the Ganesha suggest that the phenomenon happens over a much deeper volume, providing information for researchers studying the phenomenon to consider.

Crew of the Ganesha, who reported their encounter with a milky sea to CSU researcher Steve Miller.

Milky seas from space

With the Ganesha crew’s descriptions of their encounter, along with GPS-reported track logs and dates in hand, Miller was able to match satellite images from the Day-Night Band (DNB) sensor aboard NOAA’s SNPP and NOAA-20 satellites.

Piecing together the data, Miller found the Ganesha’s track intercepted the southern part of the glowing seas. Despite being far from the brightest region of this milky sea – an area where some of the clouds, also observed by the Day-Night Band sensor, appeared as dark silhouettes against the glowing waters, the Ganesha was still sailing through a region of ocean whose glow was readily detectable from 500 miles above in space.

Measuring the amount of light seen by the instrument for both the actual track of the Ganesha and a hypothetical transect through the brightest area of the milky seas provides the numbers needed to start to understand how these light displays develop. Moreover, knowing how the ocean appears from the surface gives researchers more context on what they’re seeing from space. Importantly, with the eyewitness confirmation in hand, confidence in the space-based measurements skyrockets, Miller said, as they become a viable resource to help future expeditions guide research vessels target and study milky seas in detail.

‘The biggest missing link’

Opportunities to study unresolved scientific mysteries are exceedingly rare in modern science, which is why these never-before-seen observations are so compelling, Miller said. Understanding what a satellite sees, and what’s actually happening on the ground (or in this case, the ocean) requires observations that, often, scientists just can’t get.

“The biggest missing link in our study from last year [on Day-Night Band-based milky sea detection and highlighting the 2019 Java event] was the lack of ground truth,” Miller said. “But this current study provides it. It was a great relief to get this contact from the Ganesha crew.”

Moving forward, CSU’s groundbreaking and leading research capabilities in satellite observations may provide new opportunities to learn about one of the rarest and most mysterious happenings in the ocean.

“With our ability in the scientific community to see these phenomena from space, we hope more in-person witnesses will come forward, connecting more pieces in the puzzle of scientific exploration,” Miller said.

Miller’s professional aspirations range from the high, un-trespassed sanctity of space to the high seas. “Above all, I dream of one day being on a vessel as we cross into a vast milky sea, all of us diving in and basking in its glow! I know, not very scientific, but what inspires us?”