The solution to unravel the mysteries of male infertility may be in the most unlikeliest of places: the Electrical and Computer Engineering department at Colorado State University.

Professor Diego Krapf is leveraging novel mathematical tools and sophisticated imaging technology to understand why infertility, particularly male infertility, impacts millions of people around the world.

Accomplishing his research goals could pave the way to improved treatments for some cases of male infertility, alleviating stress and health risks associated with artificial reproduction. It could also lead to the development of new contraceptives.

While infertility affects men and women equally, less is known about the causes of male infertility, and few treatments are available.

Krapf and his research team are studying why male fertilization problems occur – and how to solve them.

His recent findings, highlighted in the scientific publication eLife, provide clues for better understanding sperm cell behavior and the changes that must occur to fertilize an egg.

“This is a big health problem that our society doesn’t talk about often,” said Krapf. “If we can find a solution, even a small solution, we could help a lot of people.”

Sperm cells: they’re complicated

There are still many open questions in science about sperm – the tiniest, most unique cells in the human body.

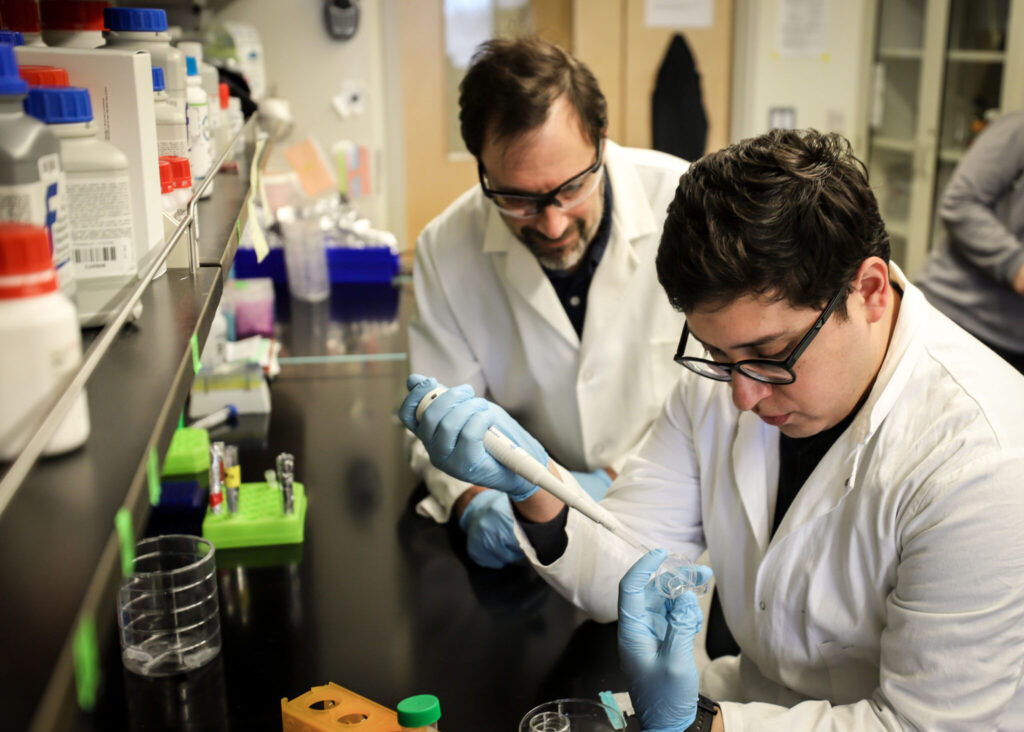

Arturo Matamoros, a post-doctoral researcher, is drawing on his background in cellular biology and biochemistry to help Krapf.

“Sperm function differently than other biological cells, and most of the tools we use in molecular biology aren’t applicable to this work,” said Matamoros.

Krapf, Matamoros, and their collaborators are investigating how sperm change to fertilize an egg in a process known as sperm capacitation. This process is the last step of sperm maturation and can be challenging to emulate in the lab because it occurs inside the female reproductive tract.

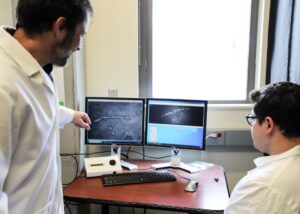

Their experiments produce three-dimensional images that help them observe cell behavior at the nanometer scale. The team can see how specific proteins move and interact within the sperm flagellum, activating a series of chemical reactions that prepare the cell to bind to an egg.

“There are many changes in cell functions and reactions that occur during these signaling events … many genes are involved,” said Krapf. “If one thing goes wrong or if one gene is defective, fertilization can’t take place.”

Disentangling these complexities is key to unlocking solutions. Krapf has observed, for example, the sperm actin cytoskeleton forming a helix structure – a three-dimensional spiral curve – and changing to bind to an egg. He said this dramatic transformation in structure has not been previously observed in other living cells, giving rise to new questions and further exploration.

Evolving area of study

Krapf’s NIH-funded research contributes to a growing body of knowledge that crosses the boundaries of engineering, biology, and physics to explore and characterize sperm. His research team includes scientists and engineers from all over the world, from Argentina to Japan.

“One of the cool things is that we all come from very different backgrounds to study this problem,” said Matamoros, who came to CSU from the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “Studying sperm is attractive to me because its research is both exciting and challenging.”

Krapf mentors three undergraduate students as part of the Scott Undergraduate Research Experience program, an initiative that pairs first-generation engineering students with faculty to conduct meaningful research.