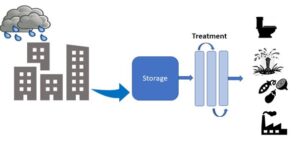

Water is a constant consideration for areas in semi-arid climates such as Colorado. Using stormwater, or the runoff from rain or snowmelt, has become an intriguing option for non-potable water uses such as irrigation and flushing toilets. Yet, with the additional pollutants that can contaminate stormwater, the process to reclaim it involves specific methods for collecting, storing, and treating the water before beneficial use.

Civil and Environmental Engineering Professor Sybil Sharvelle has published the best practices involved with stormwater capture and use, based on her research funded through The Water Research Foundation. Sharvelle’s publication entitled Assessing the Microbial Risks and Impacts from Stormwater Capture and Use to Establish Appropriate Best Management Practices provides guidance to stakeholders and the regulatory bodies who monitor and ensure the safe implementation of stormwater capture and use systems.

“The research took a deep dive into the treatment required for pathogens in stormwater and what those treatment systems should look like,” said Sharvelle.

Improving guidance for application

The project began when Sharvelle served on a panel for decentralized water systems in 2016. The panel examined several water sources, including graywater, roof runoff, wastewater, and stormwater. The resulting guidance for the capture and treatment of each water type was a good first step, but not yet actionable for the stormwater community.

“We recognized the guidance pertaining to stormwater treatment was too vague and did not include a sufficient explanation of how we arrived at our recommendations,” said Sharvelle.

Unwilling to settle for murky guidance, Sharvelle dove back into the research. After an extensive review of national data on pathogens in stormwater, her new publication is a more practical and better-defined guidance for regulations on stormwater capture and use. Sharvelle believes the research will be useful to nationwide utilities and health departments seeking to establish regulations surrounding stormwater including the appropriate treatment to remove pathogens.

Questions surrounding contamination

If stormwater is a product of rainfall, how does it get contaminated with harmful pathogens? While the major source of pathogens in stormwater is from animals, human pathogens can also enter stormwater. As stormwater flows across the ground’s surface, it gathers contaminants which can include human waste.

“There are unexpectedly high concentrations of human pathogens in some urban stormwater,” said Sharvelle. “The primary contributor is the exfiltration of sewage from sanitation infrastructure, but pathogens can also come directly from human excrement outdoors.”

The presence or level of pathogens can be difficult to predict due to sporadic events causing elevated human pathogens in stormwater, underscoring the need for Sharvelle’s guidance on stormwater treatment.

“Ultimately, where there are humans, there will be human pathogens on surfaces contaminating stormwater,” said Sharvelle. “We need to identify the level of contamination so we can treat the water appropriately for its intended purpose, from non-potable to drinking water, while considering the energy cost of treatment.”

The potential of stormwater

Sharvelle sees stormwater as an opportunity to increase the sustainability of communities, as evidenced by her collaborations at the CSU SPUR campus. Her work on water treatment research, including stormwater capture and use, is central to SPUR’s Water TAP lab in the Hydro building, where she serves as Technical Director. She also has an ongoing collaboration with the CSU Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture to develop green stormwater management systems for use in urban green infrastructure design in Denver.

Sharvelle has a history of embracing collaboration toward a better world, from researching water recycling for long-duration space travel to her work with the intersection of food, energy, and water systems.

“Civil engineering is an area that touches human lives. It embraces the concept of keeping our society growing and the economy developing while also taking care of the environment.”