Researchers in Colorado State University’s Department of Atmospheric Science have developed a tool for predicting heavy rainfall that is now used daily by the Weather Prediction Center, part of the National Weather Service.

By working with the Weather Prediction Center over the past several years, Associate Professor Russ Schumacher and his group were able to tailor the tool to suit forecasters’ needs.

A concept-to-operations success story

Excessive rainfall is difficult to forecast, and Weather Prediction Center forecasters needed a tool to help them generate Excessive Rainfall Outlooks, which are issued for the contiguous United States one to three days in advance. These outlooks predict the probability for rainfall that may lead to flash flooding, so they are important for alerting people in harm’s way.

WPC forecasters examine many different data sources in creating Excessive Rainfall Outlooks, and the number of data sources have multiplied in recent decades. Given the tight turnaround, WPC meteorologists were interested in a tool that could synthesize at least some of the data and give them a reasonable starting point.

Enter machine learning plus atmospheric science Ph.D. student Greg Herman, whose undergraduate background included computer science and meteorology. Computers are good at quickly filtering huge datasets into a comprehensible output, and Herman and Schumacher harnessed that strength for the Colorado State University Machine Learning Probabilities system.

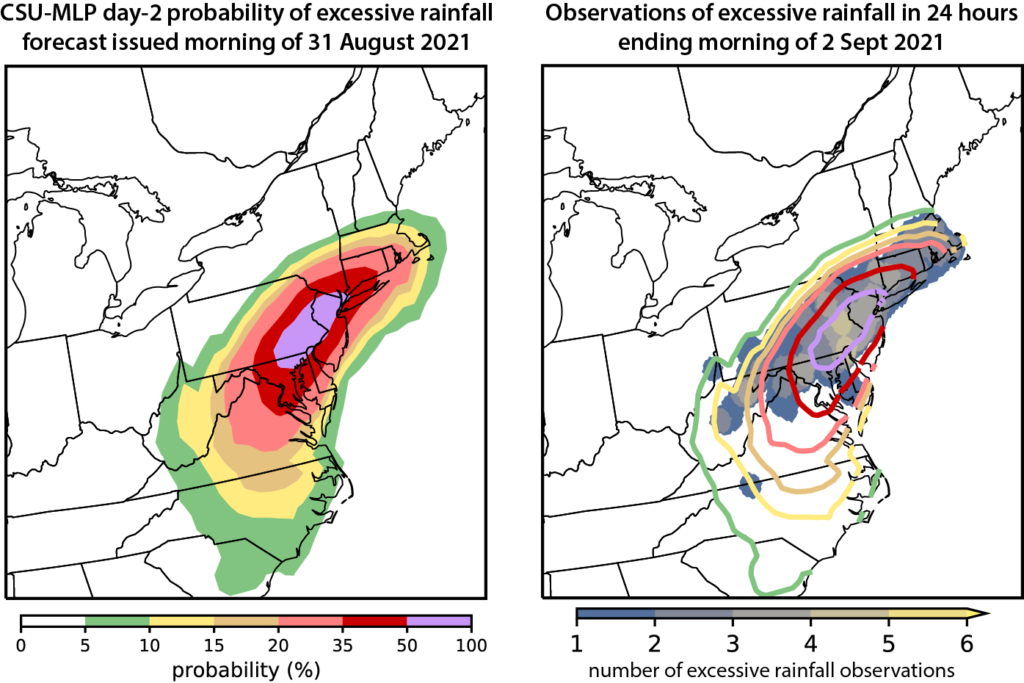

“The CSU-MLP prediction system provided the first such forecast, and represents the first machine-learning tool incorporated into WPC’s operations,” said Mark Klein, the Weather Prediction Center’s Science and Operations Officer. “Its forecasts have proven very skillful when compared to observations, and thus it has become a critical tool for our meteorologists.”

NOAA’s reforecasts, retrospective forecasts run with today’s improved numerical models, made it possible for Herman and Schumacher to train their machine-learning model using a consistent dataset. The CSU-MLP algorithm searches historical data from the reforecasts and rainfall record for conditions similar to the current weather forecast. It is able to quickly determine whether those conditions led to heavy rain.

The machine-learning model calculates the probability for heavy rain across the entire U.S., and it has adapted over time based on regional differences.

Herman and Schumacher first presented the tool to a testbed, the annual Flash Flood and Intense Rainfall experiment, in 2017. Based on user feedback from the testbed and WPC forecasters, they fine-tuned the model until it was ready for operations in late 2019. Schumacher’s group continued to work with forecasters to make improvements and released an update in 2020.

“Transitioning research work to operations at NWS is difficult; this project is one of few success stories,” Klein said. “Russ’ group has proven to be one of the best collaborators in academia that WPC has worked with.”

The forecast model is intended to make forecasters’ jobs easier by giving them a starting point to build on with their expertise and meteorological knowledge of the area.

“I’m really proud of the work my group and our partners at WPC have done on this,” said Schumacher, who is also Colorado’s state climatologist and director of the Colorado Climate Center. “It’s really satisfying to see a project go from the research idea all the way to the end product that you know somebody’s looking at every day.”

How much rain is ‘excessive’?

One challenge to forecasting excessive rain is defining what that means for a given area. A few inches of rain can be a bigger deal in Colorado than Louisiana, for example.

Forecasters go by how unusual the amount is for that area and whether it will cause flooding, which is also difficult to predict because terrain is an important factor. The same amount of rain will impact a burn scar very differently than a field.

“We’ve used average recurrence intervals as our definition of excessive rain,” Schumacher said. “Does this amount of rain typically occur at this particular location once a year, twice a year, and so on. That helps to identify how unusual the rainfall is for that area.”

Schumacher’s group has adjusted the threshold for excessive rain to make their model more accurate for specific areas, but there’s still no consensus on what constitutes excessive rain.

“The heavier the rain is, the more difficult it is to forecast in general,” he said.

With a warmer climate expected to bring more heavy rain because warmer air can hold more water vapor, the CSU-MLP tool will be useful in predicting the extreme flooding that will follow.

Schumacher’s group, including research scientist Aaron Hill, recently received funding to work on extending the CSU-MLP system’s forecast range to four to eight days. They also are collaborating with the Storm Prediction Center to apply the CSU-MLP system to other types of hazardous weather, including tornadoes, hail and damaging winds.

Development of the CSU-MLP system was funded by NOAA’s Joint Technology Transfer Initiative. Schumacher and his colleagues wrote about this model and collaboration in the paper, “From Random Forests to Flood Forecasts: A Research to Operations Success Story,” published in the Bulletin of the AMS. Herman graduated from CSU with his Ph.D. in 2018 and now works as a research scientist for Amazon.com.