This week marks the 25th anniversary of the Spring Creek Flood of July 27-28, 1997, when unprecedented extreme rainfall on the western edge of Fort Collins caused a flash flood that killed five residents and caused $140 million in damages to Colorado State University’s campus.

CSU’s Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering had a unique role in helping the community to move forward after the disaster.

Even as the waters receded from the Engineering building, two of the college’s departments were tapped to help the city understand what had happened, and what could be done to reduce the impact of similar storms in the future.

Atmospheric scientists, who research forecasting, detection and reporting of extreme weather, watched the storm develop from their vantage point on the Foothills Campus. Civil engineers, who study urban infrastructure for flood events, had front row seats as the waters inundated the lower levels of their own building.

Nolan Doesken, then assistant state climatologist and later state climatologist for 11 years, recalled that morning clearly. Heavy rains the night before had left the ground saturated. More storms were in the forecast, and one irrigation ditch he passed on the way to the Foothills Campus was already “full to the brim – fuller than I had ever seen it.”

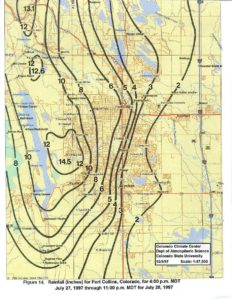

A trusted volunteer had measured an astounding 10 inches of rain in nearby LaPorte. The sophisticated National Weather Service radars in the region showed nothing so remarkable. Faculty in the Atmospheric Science department were puzzled, recalled Doesken. “Where did all that rain come from, and how had it escaped detection by the world’s best national radar system?”

As the work day ended, the heavy and extraordinarily localized rains picked up again. The western edge of Fort Collins was deluged with roughly 14 inches of rain in a 24-hour period, overwhelming the natural and man-made drainage features and building to a flash flood that swept through the city without warning.

Neil Grigg, then head of the Civil and Environmental Engineering department, said the flood followed two routes into the heart of Fort Collins.

“The water split into what you might call the Spring Creek runoff down the creek itself, and urban runoff going down the streets,” Grigg said. The Spring Creek branch would destroy a mobile home park and take the lives of five city residents in a low area near the creek’s College Avenue underpass.

The urban runoff headed for the CSU campus.

“The runoff coming down Elizabeth Street was so high there were people kayaking down there,” Grigg said. The water then cascaded past Moby Gym, the lagoon area, the library, and the Lory Student Center, where the parking lot became a lake. Eventually, it drained through the Oval and into the city’s stormwater system. [Read a more detailed description of the flood’s path through campus, and watch a video of the early cleanup efforts, here.]

Mobilizing for recovery and resilience

In the aftermath, the CSU community responded. Faculty from Atmospheric Science and Civil Engineering worked together with city leaders to understand the storm’s impact, where existing infrastructure had proved inadequate, and steps to reduce danger to life and property hazards in future flood events.

In the midst of the technical challenges posed by analyzing the disaster, Grigg was particularly struck by the psychological toll the flood had on the community.

“Because it was kind of my area of work, I decided I would organize a community meeting to discuss lessons learned. The number of people who turned out at the meeting was gigantic,” Grigg said. “We had emotional testimonies from the mayor, from emergency response people, from citizens. As an engineer, I’d normally think about it as more of a technical problem, but there’s a lot of that kind of social aspect of it too.”

Grigg remembers connecting with colleagues outside of engineering, too, as faculty across CSU worked with city officials to help the community recover and make sense of the tragedy.

Doesken collaborated with colleagues at the Colorado Climate Center to gather as much detailed data as possible about the extreme local variations in rainfall amounts. Their results showed that over distances as small as a mile or less, rainfall totals varied by as much as several inches.

Doesken was troubled by something else. On the day of the flood, he had discovered a crack in his home rain gauge; it would not read above one inch, no matter how much rain fell. He assumed that other observers with functioning gauges would report the extreme event to the National Weather Service, but later learned that none had.

A critical window for early warning of the flood danger had been missed. Determined to address this shortcoming, he spearheaded a new citizen science initiative known as the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network, or CoCoRaHS.

CoCoRaHS has grown to a network of more than 24,000 volunteers throughout the United States, Canada, and the Caribbean. Today, thousands of daily volunteer observations supplement weather radar and satellite meteorology.

Lessons from the flood led to significant improvements to the city’s stormwater management infrastructure. On campus, vulnerable basement-level areas of the Lory Student Center and the Morgan Library are protected by walls to keep future floods from entering the buildings there. And the Fort Collins stormwater department installed internet-connected flood monitoring devices at key locations so residents have access to potentially life-saving warning of rising waters.

Over time, Grigg mused, “people tend to forget.” The anniversary is “a good reminder of the central nature of our work in hydrology, stormwater infrastructure, risk assessment, and urban planning. We should be reminding the public (and ourselves) about such risks, and feeling good about our roles in finding solutions.”

Doesken shared a similar sentiment. “If you haven’t already, soon enough you’ll likely have your own flood story,” he said. “My request is — please share your story. Weather forecasts and flood warnings are better today than ever, and communications are incredible. But still people get in trouble. By sharing our storm stories and our vivid memories of past experiences, maybe others will do a better job of surviving the next storms.”