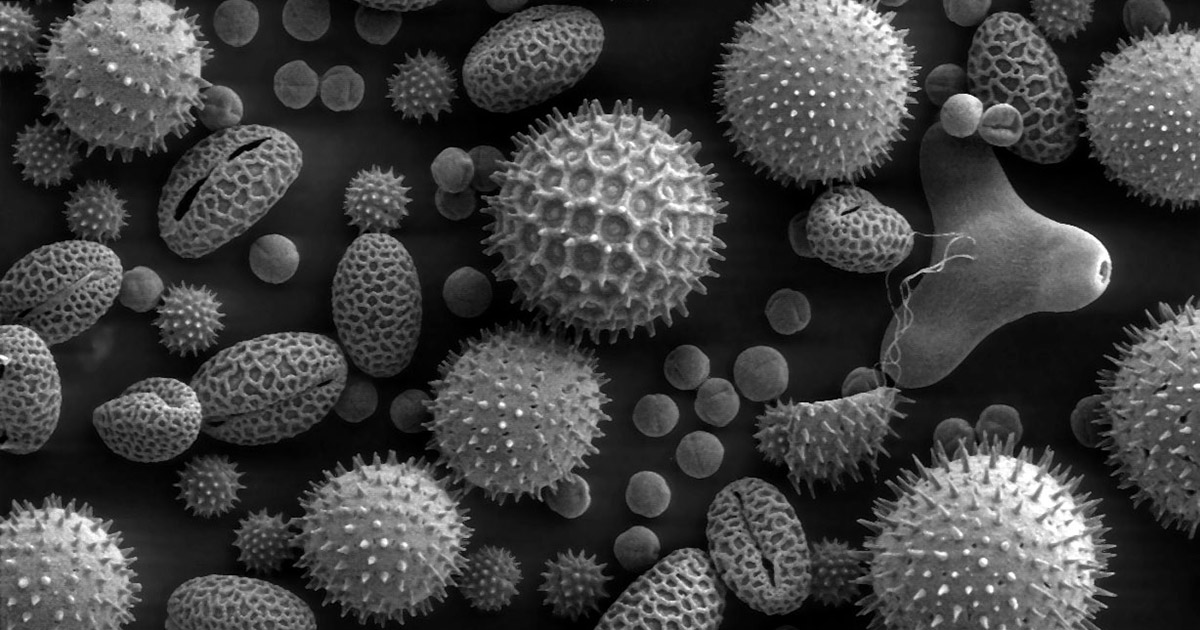

Pollen grains imaged with a scanning electron microscope. Synthetic biologists are attempting to manufacture sporopollenin, the extremely durable biopolymer that forms the outer walls of pollen grains. Image credit: Dartmouth College Electron Microscope Facility

It’s the most durable biological material you’ve never heard of: sporopollenin.

This naturally occurring polymer coats and protects individual grains of plant pollen, and it’s been found in 500 million-year-old sediments. (It’s not the stuff that causes allergies – those are proteins within the pollen itself, not the coating.)

Synthetic biologists at Colorado State University are attempting to manufacture sporopollenin in the lab using plants, and to control its properties using gene parts designed for specific functions, known as genetic circuits. Their goal is to produce coatings that could one day protect ships, bridges and other infrastructure that crack as they age.

DARPA funding

They’ll get there thanks to a $1.7 million grant from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), part of the U.S. Department of Defense. DARPA is known for funding extremely difficult, high-risk, high-reward science. The award to CSU researchers may be eligible for another $2.1 million for two additional years, if their methods prove successful.

The project’s lead is Mauricio Antunes, special assistant professor of biology at Colorado State University. Antunes will work closely with co-collaborator June Medford, professor of biology. Antunes and Medford have worked together in plant synthetic biology for 14 years. Joining in the effort from Medford’s lab will be Kevin Morey, special assistant professor of biology.

The other key player in the partnership is Matthew Kipper, associate professor in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering and School of Biomedical Engineering. A materials scientist, Kipper will help the team characterize the structure and function of the sporopollenin-like materials they make using specialized, high-resolution microscopy and spectroscopy.

Read more stories about Research at CSU.

Scalability challenges

Making sporopollenin in quantities large enough to become commercially viable is a challenge no scientist has yet overcome. This polymer is nature’s original tough nut to crack: So resistant is it to degradation, that scientists have trouble taking it apart and identifying how the polymer is formed.

“The biosynthetic pathway of this polymer is very complex,” Antunes said. “In order to replicate it, we will need to precisely coordinate the expression of several genes in plant tissues that do not naturally produce this polymer.”

If the scientists are successful, they will produce a tunable, scalable polymer that can be sprayed onto bridges, hulls and ships, making them impervious to rust or decay.

With proven expertise in making genetic circuits and inserting them in plants, the team plans to transform the tissue of Arabidopsis roots and moss, using their specially designed DNA. Then, the plants should express new genes, and produce the polymer. Plants are ideal to use because they already have a basic biosynthetic pathway in place that the scientists can build on.

“Life has existed for billions of years,” Medford said. “Plants have come up with a better way to live on our planet, than we have with concrete and metal. If we can engineer living materials, we can come up with sustainable ways to copy what life has already done so well.”