Think about reading this paragraph on your phone. It is just a story, in an app, that you are holding in your hand, nothing more.

Or is it? Think about how complex of an idea reading on a phone really is.

Someone had to develop the glass you are touching to scroll through the story. Someone else made technology that could tell when you touch the screen, how hard you touched it, and for how long. Another person built a plastic board with a spot for a battery, so that the technology that understands touch feedback gets the power to do its job.

There is the person who designed the protective case for all the electronics. Someone designed the machines that box the phone up on a factory line, a line that itself was designed by yet another person.

Someone with an understanding of technology, engineering, science, development, and even marketing had to make sense of it all. They had to learn how to work with these people and complexities, to make sure you could easily take out your phone and read this article.

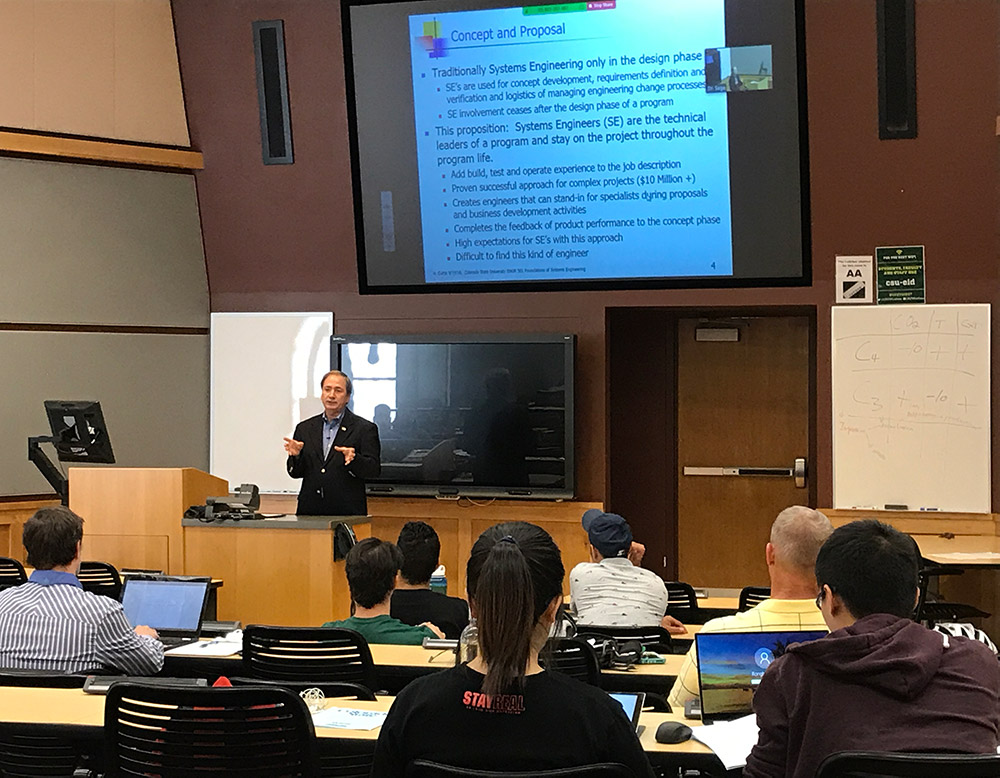

That is what systems engineering does. It is a discipline that designs and optimizes complex systems over their life cycles. The Systems Engineering Program at Colorado State University, celebrating its 10th anniversary this year, teaches students how to manage the increasing complexity of the 21st century.

The first decade of Systems Engineering

A graduate degree program, the CSU Systems Engineering Program has grown significantly over the years, increasing admissions 142 percent over last year alone. The program currently has 118 doctoral students, the second highest count on campus. However, the program started out considerably smaller.

“We started teaching our first class in my office, with chairs all over the place,” said Ron Sega, director of the program.

With a rapid start and industry support — particularly with a large donation provided by the Woodward Foundation near the beginning — the program flourished. Ten years on, the program has 36 associated faculty members, collaborates with seven university departments, and features masters and doctorate programs.

The program has seen a steady increase in the complexity of engineering projects. Broadening industry partnership has meant that diverse expertise is a requirement. Teaching a multifaceted awareness of different disciplines, including those outside of engineering, is the foundation of the Systems Engineering program.

‘The glue that holds disciplines together ‘

Systems engineering doctoral student Bo Marzolf said his experience offers a good explanation of what being a systems engineer really means.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering, he became an expert in complex military systems, earning master’s degrees from advanced Air Force schools for cutting-edge combat and satellite projects.

Despite his degrees and decades of expertise, he found that he did not have the right skillset to deal with the greater integration of specialized systems. The CSU Systems Engineering Program helped him refine his approach to integrating systems, and working with the different stakeholders of a project.

“A multifaceted approach is what systems engineers do,” said Marzolf. “Systems engineering is the glue that holds disciplines together.”

The courses he took explored how a systems engineer works through different types of interactions. That meant learning to be conversant not only with other engineers, but also project managers, marketing and business staff, and other key stakeholders.

Living with ambiguity

Steve Simske, a systems engineering faculty member, described systems engineers as being a natural flow out of team leadership. They have to be comfortable in other engineering disciplines, and understand security, sensing, and data modelling concepts that cut across disciplines.

“What I tell the students in my courses is that systems engineers need to be the second best at everything on the team,” said Simske. “Except for the parts that nobody else is in the discipline of, then they need to be the very best.”

Simske, who joined the program earlier this year, added that the coursework teaches systems engineers to live with ambiguity, and that team dynamics can become as sophisticated as the projects themselves. Engineers already in the workplace, at different levels of their careers, are learning how to work with complex systems and teams on real-world issues.

Systems engineering and industry

Working engineers in single disciplines often come into the program to earn certificates and advanced degrees, and sometimes bring their real world project concerns with them.

Simske said that students frequently asked his advice on their projects, and he tries to help where he can. They then take the information back to those projects, and Simske sometimes adds that content into his courses.

“It is a very real world in the classes,” Simske said. “You have faculty who have actually dived deep into the productization side of engineering.”

The academic world often provides quick answers to challenging theoretical and applied problems, Simske continued. Industry can provide ways to optimize solving the problem, once they know what the right approach is.

“Many of us in the program have looked at both worlds,” Simske said. “I think you are seeing a change in the polarization of skills between industry and academia, and systems engineering is a great example of that.”

Surveying industry knowledge and needs

Industry experience has played an important role since the beginning of the program. Before the program started in 2008, key government and industry members were surveyed in an effort to determine what the systems program should look like.

Government and industry experts from aerospace, energy, environment, health care, and technology all weighed in. Working with advisory groups, Sega introduced the first systems engineering courses at Colorado State University.

Through continued industry surveys and advisory boards, the program maintained close ties with industry, designing classes that balanced coursework with students’ family obligations and regular work schedules. As the program expanded, many degrees and certificates started being offered partially or fully online, in an effort to support students in managing their busy schedules.

“It’s a customer-driven program from beginning to end,” said Sega. “We periodically survey our industry representatives: Are these current courses still appropriate? Are the ways we deliver things still appropriate?”

Contributing to land-grant heritage

The Systems Engineering Program aligns with the goals laid out in the land-grant act that created Colorado State University itself, Sega said.

Practical innovation, solving real problems, support for economic development, and access to industrial classes are all parts of both the land-grant initiative and the Systems Engineering Program. As a complex world gets increasingly intricate, the program teaches students to become more competitive and driven by customer needs.

“The complexity challenges are increasing for our students,” Sega said. “Over the last 10 years, we’ve been meeting those needs, demonstrating access and excellence, and solving problems.”