Take the wheel or let the car drive autonomously? Graduate student develops driving simulations of cyberattacks

- By: Katharyn Peterman

You’re sitting in an autonomous vehicle when you notice the stop light at the next intersection is flashing quickly between red and green. Your car, relying on sensors to detect the stop lights, is unable to determine if it should stop or keep going. Do you take over and start manually driving, or do you let the car continue autonomously?

These questions guide Somayeh Aliebrahimi’s master’s research.

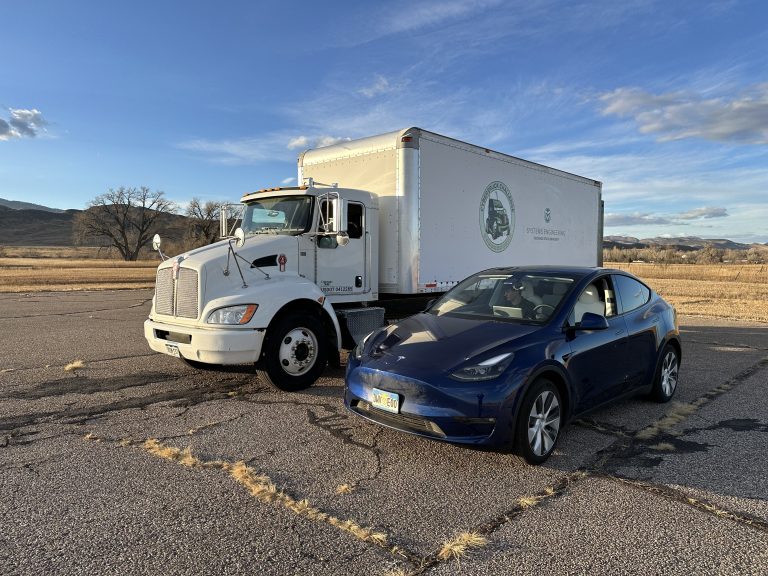

Aliebrahimi, a master’s student in the systems engineering department, conducted multiple driving simulator tests to investigate these questions with an added twist: the flashing stoplight was the result of a cyberattack.

“Autonomous vehicles are really new, and many people may over-trust the technology,” Aliebrahimi said. “Some people may not even know that it’s possible for a hacker to hack the vehicle to cause issues for driver safety.”

Driving simulations

Aliebrahimi designed four scenarios using the driving simulator in Assistant Professor Erika Miller’s Human Systems Lab.

Each scenario asked the participant to drive in autonomous mode and featured a simulated cyberattack. The attacks included slightly obscuring a stop sign with stickers so the car’s sensor couldn’t recognize it, cycling the stoplight between red and green quickly, turning the vehicle’s dashboard on and off rapidly, and blinding both the car’s sensor and the driver’s view of the road by shining a bright light on the windshield.

When these different cyberattacks occurred during the simulation, some drivers took over and switched to manual driving. Other participants kept the car in autonomous driving mode, resulting in collisions between the participant and simulated pedestrians and cars.

Between each scenario, Aliebrahimi administered a quick questionnaire to understand the participant’s situational awareness, with questions asking if they noticed various elements of the simulated environment or if they noticed the cyberattack.

“When you are driving a regular car, you have to have situational awareness about what is happening around you,” Aliebrahimi said. “With autonomous mode, people may not notice changes in the environment around them, and therefore may have a slower reaction time to potential cyberattacks.”

At end of the experiment, Aliebrahimi asked participants to take a survey investigating their level of cybersecurity awareness.

“We found that there was a connection between people’s cybersecurity awareness and level of their situation awareness while driving in autonomous mode,” Aliebrahimi said.

Education as threat deterrent

Aliebrahimi found that for some participants their lack of response to the cyberattack was due to limited awareness of the possibility of cyberattacks. Some participants also believed the cyberattack was a problem with the car instead of from an external threat.

Ensuring that future drivers are aware of the threat of cyberattacks, and can respond to one quickly and safely, is a goal of Aliebrahimi’s.

“We need to, as researchers, teach people about the possibility of attacks,” Aliebrahimi said. “A really helpful way to mitigate consequences from cyberattacks is simply to inform people about them.”