Two years ago, Susan De Long did not expect to become an expert in wastewater epidemiology, but now she considers it to be part of the new normal.

Since the summer of 2020, the Civil and Environmental Engineering associate professor and Carol Wilusz, a professor in the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology, have led wastewater testing to detect the virus that causes COVID-19 on campus and for the state of Colorado. While the state program expands, De Long, Wilusz and a talented team of CSU scientists are working to improve the process, to protect public health and develop the technology to spot future viruses faster.

“This is going to be part of business-as-usual public health monitoring in the future, and the way to get there is to make it cheaper and easier and more useful,” De Long said.

Taking the community’s temperature

Watching viral spikes in wastewater correlate with increased COVID-19 cases for the past year and a half has reinforced the value of wastewater monitoring, De Long said.

“It’s incredibly useful as a barometer of the relative levels of infection in our communities, and it’s effective independent of people’s ability and likelihood of getting tested,” De Long said.

Because SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is shed in feces before the onset of symptoms, wastewater testing provides an early warning when cases are about to climb. Community leaders can use these data on whether infection rates are trending up or down to implement policies to protect public health.

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment has secured funding to continue the state wastewater surveillance program until at least Summer 2023. They are working to expand from the original 21 sampling sites to increase geographic diversity. Samples are sent to CSU or the state public health lab for initial testing. The program’s current capacity covers roughly 60% of Colorado’s population.

Scientists with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment lab conduct whole genome sequencing on all positive wastewater samples to detect virus variants, such as delta and omicron. Though the amount of virus or variant in the waste stream cannot be used to determine the number of cases, it provides crucial proportion and trend data.

“Our local public health partners use COVID-19 wastewater data, in conjunction with traditional surveillance, as an early warning sign. Based on trends in the amount of virus and the variants detected in the sewershed, they can adjust COVID-19 response in their communities,” said Rachel Jervis, foodborne, enteric and waterborne diseases program manager at CDPHE.

Planning ahead

While the campus and state wastewater testing programs have functioned well as part of the overall pandemic response, De Long and her collaborators want to streamline the process so it can be applied more broadly. Through a grant from the Anschutz Foundation, facilitated by the Office of the Vice President for Research, they will develop a new sampling device that will make collecting wastewater safer and more efficient while improving data quality.

Right now, sampling on campus involves hoisting large tubs containing several gallons of wastewater through manholes, mixing the contents by hand and pouring it into little tubes. The process is labor intensive and cumbersome for collectors who must wear full Tyvek suits to protect them from exposure to biohazards.

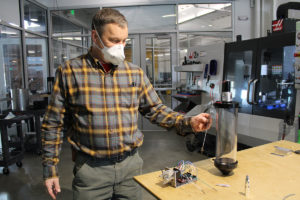

As part of the Anschutz Foundation project, John Mizia, a research engineer in Mechanical Engineering and director of the Rapid Prototyping Lab, is working on an automated sampling system that will be smaller, lighter and integrated into manhole covers. Instead of taking samples every 15 minutes, this system will collect continuously for a more representative sample. It also will thoroughly blend the collected wastewater, reducing the volume needed for an effective sample while improving the data it will yield.

“When a technician shows up to the test site, the system homogenizes the collected material, and the technician can choose whether they want 50, 100 or 200 milliliters of material,” Mizia said. “All of this happens under the manhole cover, with little user interface.”

These features alone would significantly improve wastewater testing, but Chris Snow, associate professor in Chemical and Biological Engineering, envisions a built-in filter to separate and concentrate SARS-CoV-2 virus particles, or virions, to be taken back to the lab for PCR analysis. Snow is developing a virion-capturing technology using engineered porous crystals composed entirely of protein building blocks.

“We’ve discovered that these crystals are particularly good sponges for taking up DNA and RNA,” Snow said. “We will use these crystals like molecular pegboards to install proteins that can tightly capture CoV-2 virions.”

Snow is not aware of any other researchers engineering crystals to attract virus particles. By combining this novel biomaterial discovery with advanced device engineering, this project would remove many of the technical challenges to virus surveillance and enable it to be scaled up to cover more places at relatively low cost.

De Long said this method could be especially useful for monitoring at the building level, where people live or gather in close proximity and are more vulnerable to the rapid spread of viruses. Think schools, dormitories, nursing homes, prisons and apartment complexes.

It also could be adapted to detect other, yet undiscovered viruses.

“The same technology could be readily updated for the detection of future threats,” Snow said.

“The idea is to be prepared,” De Long said. “This is part of a new pandemic preparedness infrastructure, so that we have these low-cost devices that can be deployed widely and used with minimum labor, and the next time we hear about a new virus, we’re able to rapidly adapt these to screen for that and catch it much earlier.”