Where There's Smoke...You'll Find Dr. Emily Fischer

The CSU professor has been named a scientist to watch.

November 13, 2020

CSU

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]

Colorado’s 2020 fire season has been awful. The Pine Gulch Fire became the largest fire in Colorado history in September after burning 139,007 acres — a record that didn’t last long, because the Cameron Peak Fire has scorched 208,663 acres (and counting). We’ve seen the smoke, felt the ash as it fell like an apocalyptic snow globe over the Front Range, and we’ve breathed it in acrid, choking clouds of smoke.

What does that gray-brown smoke do to our lungs and overall health? Short answer, we’re not sure — but we have incredible people working to find out.

Colorado State University Associate Professor Emily Fischer put together a massive project called WE-CAN during the summer of 2018 that studied wildfire smoke more intensively than had ever been done before. The project went well...so well that Fischer was recently named one of “10 Scientists to Watch” by Science News, which recognizes mid-career scientists age forty and under (Fischer turned forty in October) who are making major contributions in their field.

In 2019, she won the James B. Macelwane Medal — one of the highest honors bestowed by the American Geophysical Union — and atmospheric-science graduate students picked her as Professor of the Year, so she’s clearly doing a lot of things right.

But Fischer doesn’t feel comfortable being singled out for so many accolades.

“Part of my reluctance in having it be too about me is that we just do too much of that in atmospheric science. That sounds weird for someone who just got a bunch of awards to say, but all this work is done on these big teams, and it’s better for society and for students and for everyone to know that science is a team sport,” she says, laughing.

Fischer is clearly winning at this sport. After Science News named her a person to watch, we caught up with her to talk about her Western Wildfire Experiments for Cloud Chemistry, Aerosol Absorption, and Nitrogen study (yes, WE-CAN is a lot easier), as well as her other work...and her life.

Marty Coniglio: Your WE-CAN study was for the 2018 fire season. How has the 2020 season been for you?

Dr. Emily Fischer: On a personal level, I have small children...I think having the smoke in town makes us realize how close to cracking we are with COVID when you start to take away outdoor activities. My children are five and eight years old, and I am a high-energy human who needs to go for a run [laughs] or something in order to not be annoying.

That has been very hard for us. It’s also upped the importance of decision-making; we’re all burdened during COVID with every decision carrying weight that it never carried before. With COVID, everything is a risk measurement: Do you go do this, or do this? And then all of a sudden there was another decision of, okay, what is the AQI [air quality] threshold for my family? Where I say, okay, you don’t go run around outside. And I set that at 100, because it was easy for my nanny to remember, and my older daughter seems to be more sensitive to the smoke, so above that she was feeling pretty crummy.

The other thing I think we need more of — that I personally found hard — was people saying, “What do I do?” There is a communication breakdown; people are needing to make decisions and they don’t know how to make them. My friends asked me, “As a mom, what are you doing for your kids?” So I say, “Okay, let me explain the AQI, and they’re like “no, no...what number? What monitor? What exactly for my family?”

So we need to get better at real clear guidance. Even if we’re unsure, we need to err on the side of caution and get clear on the guidance for people with smoke.

How are your studies helping with that?

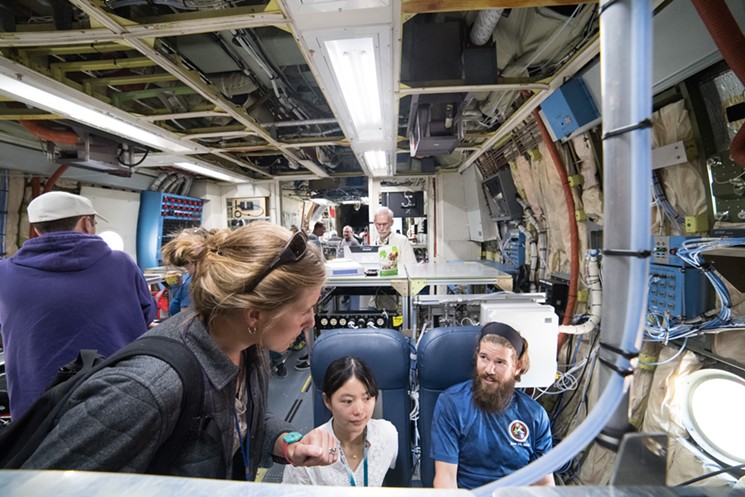

During a typical flight, we’d go behind the fire, and there’s two reasons for that: You want to measure the air that’s going into the fire and measure what’s in it as cleanly as possible, and also you want to see the fire. Then we would turn into the smoke plume as quickly as was allowed, because there may be restricted air space to allow aerial firefighting, or as quickly as our pilots felt it was safe. Then we would basically mow the lawn, with the plane cutting back and forth through the smoke to see how measurements changed with time and distance. When we’d run out of smoke, we’d head back to the beginning to do it all again to get a second sample.

Now, as far as what sucking this stuff into our bodies means...

What is in some ways harder is my understanding of the health impacts of smoke exposure, and also recognizing what we don’t know about that. People are asking these kinds of questions, which we don’t know the answers to, and I wish we did. All of our smoke-health research has been focused on acute exposures...so like, smoke comes to town for a week, what happens? Not, you’re exposed to smoke for 72 days and maybe you were exposed last year for 72 days...where it’s becoming more chronic. We don’t have great answers for these chronic exposures.

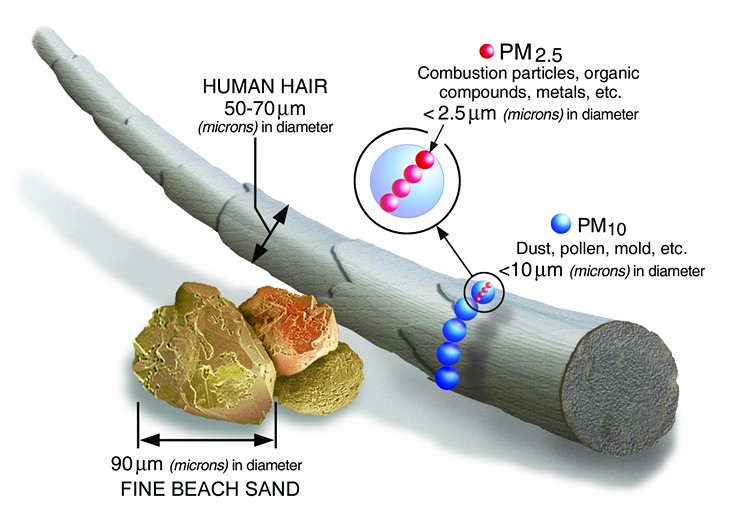

You’re optimistic that the data you got during WE-CAN is going to help public-health professionals learn more about what dangers exist in wildfire smoke. Most of the air-quality warnings we get are for “fine particulates,” specifically PM 2.5, which are airborne pieces of material about 24 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair.

From a public-health standpoint, what we are doing with the WE-CAN data is, we have some estimate of PM2.5 mass. So we say, okay, now when PM2.5 is this, and the smoke age is about this, what else is in the smoke? How much benzene is there, how much acrolein is there, how much hydrogen cyanide is there, how much of these toxic air pollutants (as defined by the EPA) is also there?

We’re using that so that we can try to figure out if it’s just the exposure to fine particulates or are there other things that the health officials might want to measure — like formaldehyde — more routinely so that they can understand those exposures and the chronic long-term health effects of exposure to smoke.

Our outlook for future seasons is anything but awesome. Climate research is painting a portrait of a fiery future.

Beyond teaching, research, running and raising your family, do you have time for anything else?

There are two things I’m doing now. PROGRESS is one effort to support undergraduate women [in science]. I try to work on things that I know how to do, and I am good at logistics, and I am a woman. I try to figure out where I can understand the problem and where I can help. I thought, we’re doing an okay job with mentoring, and I can see some neat initiatives at the graduate level and at the post-doc level. But what can we do to really help undergraduate women get through that first and second year, where they’re often going to drop out and they might not feel like they belong?

I think about me as an undergraduate meteorologist. I did well, and I lived with all my female classmates. There were four of us, and everyone else was a guy. And if I hadn’t had them, I’m not sure I would have had that sense of belonging in the same way.

PROGRESS came from the Earth Science Women’s Network, and was developed by a group of us that sit on the board. Then we needed a social scientist team to help us make sure what we did was effective and grounded in best social science research, and also to rigorously test what we were doing to see if it was making any difference or just making us feel good about ourselves.

Now PROGRESS is on the Colorado Front Range and in the Carolinas. Next year we will open it up in Georgia and two regions in Texas, and then a year and a half after that, we will invite two other U.S. regions to initiate the undergraduate mentoring program. The goal of this next phase is to make the program more transferable to other universities and to really serve women of color. It’s a little intimidating and terrifying, but I think it’s going to be fun, because in the fall we’ll have about 2,000 students.

How does this support system provide an upside for the earth sciences?

There is evidence that diverse teams are just more effective. They come up with solutions faster, those solutions are better, more easily implemented, and so diversity is really, really important for applied sciences. If you don’t have a diverse team, you risk asking the wrong questions, you risk not even working on the right thing, and not having your science serve society. Which is what I think everybody in the earth sciences wants. I really feel that earth scientists in general are great people who want to serve society, but if you don’t have society represented on your science teams, you’re just not going to do that.

You’re not going to identify the right problems that need to be solved, you’re not going to identify the right intervention points, you’re not going to be able to communicate. There are so many ways that the breakdown between science and society could happen. You might even be employing the wrong methods.

What is the other initiative that you are taking on?

I’m working on sexual harassment...that’s the other project that I have. We started with the WE-CAN team, and we surveyed three other large atmospheric-science field programs on past incidences of harassment, and then incidences of harassment during the field program. The goal of that is to test the sexual-harassment training that happens before a project in the context of the actual field program.

Field programs are really interesting if you think about it, because they are really high-stress, they are away from people’s support structures, often they can be in very remote environments, so if you look at where they’ve had some high-profile incidences, they have been in Antarctica and places like that.

Field programs are extremely good for your career! So if you pull off something like WE-CAN, I mean look at this, right? I get these awards and these things and I get lots of papers, so if you pull off something like this or you are involved in it, it’s really good for your career. You have these enduring collaborations...but if you are the target of harassment in such a setting, the stakes are extremely high, creating pressure to not report because the stress is so high given the potential benefit of being involved in the project that’s so influential on the path of your career.

These teams when they are functioning well are also these amazing points of intervention. If you look at the WE-CAN team, it’s six different universities and the National Center for Atmospheric Research, so if you figure out best practices and all of those people are on board, BOOM, it spreads really fast to big universities, and they can adopt it in their settings.

After figuring out the coordination between all of the institutions and jurisdictions, how do you use the team and the community around that team to build a network of men who are invested in this? Men who are more comfortable talking about it. My WE-CAN guys are not as comfortable as I am now, but they are so much more comfortable talking about this issue than, I would say, comparable colleagues.

We went through a training, they trust me, I said, “Hey, guys we gotta figure this out. Be on my team, just like you are for WE-CAN, to help us figure out best practices,” and they’re like “Okay.” I removed the blame piece; I think there are a lot of men who would be proactive or report this if they weren’t so worried about saying the wrong thing.

So that’s what I tried. I thought, “Okay, this team of people I trust, who I think are awesome, who come from a diversity of backgrounds. Can we pilot some new things on sexual harassment?” When I picked the team, I knew these are all people who I know care about their students — so whether they’ve ever engaged on anything related to harassment before, I know they care about their students. So I can say to them, “The goal here is to protect our team, and in doing so, let’s pilot best practices and see how they work.”

I have an article about this under review in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society that outlines what we did and what we found.

Many climate researchers are warning of even worse fire seasons in the future. What is it that leads to such a dire forecast?

My student Steve Brey, his dissertation was on climate and fires, and his most recent paper that just came out this year looks at different eco-regions across the western U.S. and looks at the past environmental conditions that predict large burn-area years. If you look at the Rocky Mountains...the one thing that really predicts burn areas in past seasons is aridity.

My family actually ran from the Cameron Peak Fire on August 13; we were backpacking. I have been joking with Steve that I am living in his dissertation. It’s right on cue with past years that have had a particularly dry June, July, August — we have our highest burns areas. That’s what predicts the year-to-year burn area in the Rocky Mountains.

What’s really depressing, then, is to look forward with that, because the one thing we really know from climate models is an increase in temperature and an increase in aridity. So if there is enough fuel to burn, and if these past relationships hold, the season like we just had is what it looks like going forward.

And “Scientist to Watch” Emily Fischer will be watching.

Who should Marty Coniglio talk with next? Send your suggestions to [email protected].

BEFORE YOU GO...

Can you help us continue to share our stories? Since the beginning, Westword has been defined as the free, independent voice of Denver — and we'd like to keep it that way. Our members allow us to continue offering readers access to our incisive coverage of local news, food, and culture with no paywalls.

Can you help us continue to share our stories? Since the beginning, Westword has been defined as the free, independent voice of Denver — and we'd like to keep it that way. Our members allow us to continue offering readers access to our incisive coverage of local news, food, and culture with no paywalls.

Meteorologist, musician, mutt lover, airplane pilot, man of the outdoors, Marty Coniglio has been a fixture in Denver media since the 1980s. One of very few news/weather anchors to work at the ABC, NBC and CBS affiliates in Denver, Marty has covered every major weather event in Colorado for a generation. He is currently focusing on expert weather analysis for legal cases and independent media projects.

Contact:

Marty Coniglio

Follow:

Instagram: @martyeconiglio

Newsletter Sign Up

Enter your name, zip code, and email

I agree to the Terms of Service and

Privacy Policy

Sign up for our newsletters

Get the latest

News,

free stuff and more!

Trending

Use of this website constitutes acceptance of our

terms of use,

our cookies policy, and our

privacy policy

Westword may earn a portion of sales from products & services purchased through links on our site from our

affiliate partners.

©2024

Denver Westword, LLC. All rights reserved.

Do Not Sell or Share My Information

Do Not Sell or Share My Information